What is the concern about ‘greenwashing’?

According to Forbes, ‘greenwashing’ is a form of marketing spin whereby organisations seek to persuade the public that their products, organisations and policies are environmentally friendly, when in fact they are not. This causes problems for those outlining their sustainability credentials to a skeptical world.

The obvious concern from stakeholders is that these types of disclosures are misleading.

From a corporate perspective, this can be seen as short-term thinking, on the basis that ‘the truth will out’ and what will be lost as a result, is the trust of stakeholders and trust is far more valuable than any short-term green credentials.

From an enterprise-wide risk management perspective, greenwashing is bad for all aspects of the organisation and the stakeholders involved and the real problem will be the lack of trust greenwashing proposes.

What are the concerns with ESG disclosure?

The long-standing concern regarding providing non-mandatory ESG reporting, is that an organisation opens itself up to further scrutiny. Every disclosure becomes a ‘hostage to fortune’ depending on what might happen in the future to bring ‘innocent’ data into focus, with the benefit of 20-20 hindsight.

In this context, any disclosure suggestion has to pass a ‘why would we do this?’ test.

What are the arguments for ESG disclosure?

The arguments for ESG disclosure are the same for all corporate disclosures. The agency problem associated with publicly listed companies means that management have more information than shareholders or wider stakeholders, causing an imbalance in informational power.

Disclosure is therefore good, because it ensures transparency and allow stakeholders to make decisions on whether to engage with organisations based on a common set of data.

ESG reporting and stakeholder expectation

Each organisation has a unique set of stakeholders, depending on its corporate structure (public, private, mutual, not-for-profit), industry sector and regulatory environment. All organisations however, have some form of external business partners, customers, employees and board or management team. To this may be added, investors, regulators, ESG rating agencies, insurers or auditors. Each group of stakeholders will have differing levels of influence and will ultimately shape the context within which an organisation determines its sustainability strategy. This sustainability strategy will drive what each organisation prioritises and reports on.

In an ideal world, organisations would have regular objective meetings with stakeholders to ensure the ESG disclosures are aligned with expectations. In practice, there is a need to provide an aggregated view of what management believes is most relevant. This is where the greenwashing risk enters. How does management determine what is relevant and appropriate to disclose and is there temptation to accentuate the positive and leave out the ‘non-correlating’ facts that do not fit with the overall storyline?

The advantages of standardisation and verification of ESG reporting

Investors and stock exchanges are pressing for both standardisation and verification of disclosures. This is the best way for outside stakeholders to compare and contrast the ESG performance of different organisations and to hold management to account. The advent of global standards such as, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), established under the direction of the IFRS Council, is expected to drive standardisation. Organisations will be expected to provide a core set of ESG performance metrics, plus a number of sector-specific metrics.

Currently, many organisations are free to report on their ESG performance in their own way and the challenge of comparing ‘apples and pears’ is exacerbated by a wide range of ESG rating organisations, each providing their own ESG scores, which don’t necessarily correlate.

External verification is likely to be initially driven by stock exchange requirements, but over time, it is likely that those that don’t provide certification or audit their disclosures will stand out as the exception.

The disadvantages of standardisation and verification of ESG reporting

Every action causes a reaction. So, what might be the downside of these developments? In this case, we could anticipate a disconnect between templated ESG-disclosures and the ever-evolving nature of sustainability programs, that need to keep evolving to address the ESG challenges facing particular organisations.

ESG reports will continue focusing on strong audit trails and internal controls rather than data sources that allow external certification and as a result, this could lock-in a specific set of metrics which could become ‘boiler plate’ over time. One could imagine that, as a result, ESG reports become ‘tame’, in terms of driving change, and lose their cutting edge.

How to navigate through the uncertainty?

The answer is clearly – with care.

From previous experience, the organisation I worked for recognised the coming winds of change and wanted to prepare for additional scrutiny. This meant strengthening our controls over non-financial reporting. We began by mapping our processes and documenting our reporting steps. Internal Audit were asked to provide an assurance review, to highlight areas where controls could be strengthened for future reporting and in preparation for enhanced scrutiny.

The risk management function helped management think through the decision on what metrics to disclose beyond what is currently mandatory. For these voluntary disclosures, there isn’t a right or wrong answer and so it was ultimately a risk-based decision.

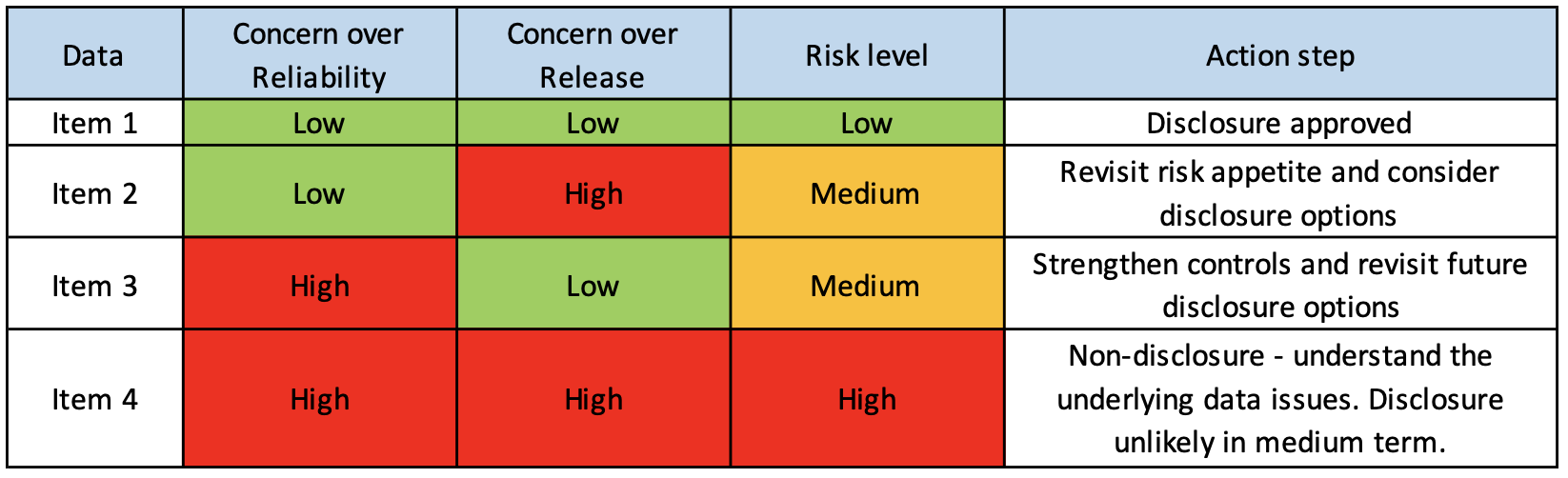

The company adopted a risk-based approach considering two simple criteria.

‘Concern over Reliability’ (high, medium, low) whether the supporting data could not be adequately assured (i.e. not representative of a sustained ‘story’ or trend, or too volatile to be meaningful).

‘Concern over Release’ (high, medium, low) whether disclosure could lead to wider implications of concern for the company. Data owners were asked to provide the scoring, with justifications.

Anything scoring ‘high’ on both considerations was omitted from this specific report, and would be revisited in future, as confidence over data and disclosure grew. The process can be summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Example of disclosure risk assessment grid

Conclusion

Despite pressures, there may still be a place for a corporate Sustainability Report in a post-standardisation and post-verification world. The element that gets lost in the drive for transparency and verification is the ‘telling of management’s story’, which is about the ‘why’ behind the sustainability strategy and how these fit within the organisations core principals. It is important this does not get lost in the rush to verify.

Alex Hindson is Partner and Head of Sustainability, Risk Consulting at Crowe UK LLP